Tuesday, August 28, 2007

Friday, August 24, 2007

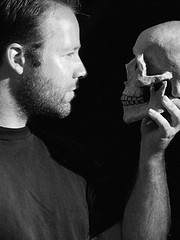

Spine, Not Skull

I just read a great essay by Wayne Narey, a fellow at Arizona State. It focused on a videotape he was asked to watch about teaching Shakespeare (‘cause why else would this story end up in my blog?). He was nonplussed, to put it politely. In what sounded like a very cheap video made by an uber-academic, it suggested teaching ROMEO AND JULIET by asking questions of the students like, “Pretend you’re Romeo – what would you do in the situation?” Balogna. I quote from his article:

‘"But," I can hear the teacher asking, "don't we need to make it relevant, to give them INFORMATION, details, and get them INVOLVED?" In a word, no. Help them to appreciate the play and its greatest asset, the language, which usually teachers perceive as the greatest liability in teaching Shakespeare's plays, and which, it becomes assumed, presents problems for both the teacher and the student. The language represents the point where the teacher must begin, whether at the high school or college level. Vladimir Nabokov makes this point through his character John Shade in the novel Pale Fire, offering the best piece of advice I've ever heard regarding Shakespeare: "First of all, dismiss ideas, and social background, and train the freshman to shiver, to get drunk on the poetry of Hamlet or Lear, to read with his spine and not with his skull." As a university professor, of course, the fictional John Shade doesn't live in the real world. At some point in weeks of study on Shakespeare, a teacher must offer something about ideas and, it must be admitted, social background. Writing his novel in the early 1960s, poor Nabokov had no idea about to the New Historicism school of criticism, and so did not, in his ignorance, know that Elizabethan culture really penned and staged Romeo and Juliet, much as the New York of the early '60s wrote Bernstein's score and choreographed "West Side Story." Anyone creative in those days wrote musicals with a lot of dancing on rooftops.’

I couldn’t agree more (especially that “dancing on rooftops” bit). First of all, why are we teaching Shakespeare in the first place? Is it so that students can somehow see that they have the same problems that Elizabethan kids had? No. Is it so that they can learn a great story that will impact their lives? Not really. So, why?

Because no one in the history of the English language (quite a bit of which he created) has been able to express the Universal themes, emotions and characteristics of the human being as has Shakespeare. He was in no way original in his choice of story, but he presented those stories in such an affecting way that they have lasted throughout the centuries, as most of his source material has not.

The study of Shakespeare can be viewed in some ways through a “Dead Poet’s Society” view of the glory of poetry and it’s expressiveness, but while “Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow” may be able to stand on it’s own as a piece of thematic poetry, one cannot say the same for the equally-if-not-more famous “Is this a dagger which I see before me?” from the same work. One could argue that the study of drama in it’s truest form should be one of the requirements at school, as the basis of drama and theatre is to “hold the mirror up to nature” and show us ourselves. Film, the modern derivative, is today far more frequently used as pure senseless entertainment and sheer spectacle rather than really showing us who we are as human beings and the gamut of our emotional landscape. What, especially in today’s society of apathy, warfare, divorce and laziness, is more important to instill in our youth than the self-realization of emotion in their lives. We shut down so quickly these days that any chance to experience a healthy emotional life should be welcomed with open arms.

This is one of the main reasons that “Brave New World” is one of my top ten books: we’re moving so much closer to Bokanovsky’s Process and the lack of genuine feeling that the Savage finding and cradling the Complete Works of William Shakespeare and using it as his Bible is no coincidence – The Complete Works is essentially a Bible of Human Emotion, something profoundly lacking in Huxley’s dystopic morality tale.

Pick any one of Shakespeare’s plays and you will find, if not every human emotion represented, then most. But perhaps the most notable work is Hamlet – every emotion is on display here from anger, love, jealousy, sadness, envy…. The list goes on. It’s no wonder that Hamlet is his most popular and oft-quoted work – of course, it doesn’t hurt that it contains some of the most concise and beautiful poetry in the folio. I’ve written about it before, but it bears repeating:

To be, or not to be: that is the question:

Fight through the haze that immediately clouds the brain when hearing an all-too-familiar phrase and try to think of the MEANING and not just the words. “Live, or die: which shall I do?” Nary a person on the planet has not thought this at least once in their lifetime.

To die, to sleep;To sleep: perchance to dream: ay, there's the rub;For in that sleep of death what dreams may comeWhen we have shuffled off this mortal coil,Must give us pause:

But obviously, not everyone on the planet has made the decision to off themselves. “To die; and to re-awaken in another world…… hmmm… not knowing whether that world will be a Heaven or a Hell, I’d probably better re-think this whole offing myself thing.”

This is some heavy thematic material. “Life and Death,” though a cliché phrase in today’s society, is really the end-all and be-all (another Shakespeare-ism, incidentally). What else is there? Okay, taxes, but what else? Nothing. And as death is such a palpable concept, especially in our younger years when we first become cognizant of mortality, this speech above all others is one that should not be “read with the skull,” but indeed, with the spine. It is to be felt in order to be understood. Such is the case with all of Shakespeare’s work: the feeling is the understanding.

Is it therefore my suggestion to teach death to high school kids? Of course not. The point is to CONNECT with students. And connecting emotionally is the best way to connect with anyone, especially teenagers who don’t think that anyone understands what he or she is going through. Not only do we all know what they’re going through, but so did people in the 1500s and beyond. That connection to similar emotions creates an understanding, which in turn creates an interest.

Interested students? That’s a pretty good starting place in a classroom, isn’t it?

Posted by

Matt

at

5:12 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: classroom, emotion, Hamlet, Nabokov, Shakespeare, skull, spine, teaching, to be or not to be, tomorrow